Overcrowding, poor food, lack of medical care, brutal treatment from warders – these were some of the vectors transmitting tensions that broke out into violence. When Xia Wenzhi opened a cell in Jiangsu No. 1 Prison, he was assaulted by all three prisoners, who attempted to steal his keys. In the ensuing scuffle, he lost an eye and blood poured through the socket. Later, his other eye was seriously injured in a violent incident that ended his career as a warder.

More often than not, violence was used specifically in order to escape. For example, In Anhui No. 1 Branch Prison in Huaining prisoner Wang Yucang on the evening of 23 December 1937 demanded to be escorted to the latrines, and this was the start of a riot in which lanterns were smashed, the warder was tied up and pressed to the floor and his mouth stuffed with a handkerchief, and cell doors were destroyed. When the alarm was raised, prisoners fought the warders with rice bowls, and finally kicked open the main gate and fled into the night. Thirty-two prisoners, some awaiting trial, disappeared, and the investigation that followed highlighted the weakness of existing wooden doors, the fact that the force of warders was at half-strength, the inexperience of newly-hired warders who were still untrained, and the practice of keeping weapons locked up in the director's room where they could not be got at.

Escapes were less frequent in new prisons, where security was much tighter than in local gaols, but they still occurred regularly throughout the republican period. In Fujian No. 1 Prison, as two groups of prisoners were returning from the workshops to their cells in September 1929, along a corridor that passed by the main office, several prisoners created a commotion and three men took advantage of it to penetrate the storeroom and seize weapons. They attacked a warder who tried to raise the alarm, stabbed him in the arms and legs and cut the telephone line. A deputy director who intervened was kicked in the chest and legs, and collapsed on his knees coughing blood before he lost consciousness. One warder was repeatedly stabbed in the face, and several others were punched before the rioters started breaking up the main gate: twenty of them disappeared, leaving behind chaos as warders tried to keep the remaining prisoners under control.

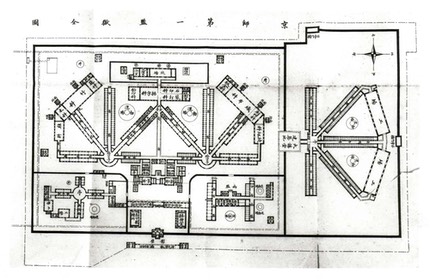

Even model prisons had their reputations compromised by escape attempts. In August 1927 Jiangsu No. 1 Prison was forced to ask for police reinforcements in the middle of one night when dozens of prisoners ran amok. As a subsequent investigation showed, two pairs of sharp scissors had been smuggled from the workshops back to the cells and the prisoners used them to dig a hole through a half-metre-thick wall. The warder on duty had been bribed and turned a deaf ear. Shortly after midnight on 30 August, about twenty prisoners managed to make their way through the hole and to the door of the prison block, where they overwhelmed and tied up the warder, took his keys and opened other cells. As the alarm was raised, a group of prisoners found a room with guns and ammunition, but after one of the leaders was shot in a set-to with the warders, they were gradually forced back to their cells. Those hiding in workshops and latrines were caught, and not a single man was missing at the final count. Overcrowding after the Guomindang occupation of Nanjing and understaffing were explicitly blamed for the unrest by the acting director.

Most prison escapes took place in timesof natural catastrophe or military unrest. In January 1932 Japanese marines ordered ashore in Shanghai met opposition from government troops in the poor residential district of Zhabei and in retaliation, the area was bombed. A major attack on Shanghai's defences led to fierce battles that only ended with an armistice in May 1932. The bombing of Zhabei created havoc in Jiangsu No. 2 Prison, where the authorities reported that the prisoners were 'ready to start making trouble'. Asking for advice from the Ministry of Justice, the authorities were ordered to step up security to prevent riots or escapes. More examples are given in the section on local gaols below, as well as in the next chapter which covers the war period.

However, violence and the fear of it also marked relationships between the prisoners themselves. Where ledgers detailing the prisoners' punishments have survived, they reveal an atmosphere of latent violence: in one of the local court gaols in Shanghai, prisoners were reprimanded, deprived of visits or restrained by handcuffs or leg-irons for a set number of hours for quarrelling, shouting and exchanging insults; 'mutual fights' (huxiang ouda) were frequently mentioned. A major threat for new arrivals, especially in local gaols, came from their fellow inmates. Informal cell bosses (laotou or pengtou) could bully, blackmail or use other methods to put pressure on new prisoners. In an overhaul of the Zhenjiang county gaol in Jiangsu province, several cell leaders (longtou) were sent to court for maltreating cell-mates. In one case several older prisoners colluded with the warder Lei Xiying to extort money from an opium smoker, Yu Jieping, while cell leaders were found to be beating new arrivals with sticks. Opium smoking by cell leaders was common: Zhenjiang county gaol sent six cases to court, as the procurator attempted to interrupt the supply by arresting four relatives found to be smuggling it into the gaol during visits. Similar problems also characterised new prisons: in Jiangsu No. 3 Branch Prison a cell leader was discovered in September 1927 to have colluded with a warder to extort money from prisoners. This problemwas recognised by the Ministry of Justice in 1935 when it ordered quicker processing of cases awaiting trial and sentenced criminals to be sent to new prisons to avoid the problem of cell bosses whose incorrigible 'evil nature' was a threat to new arrivals.